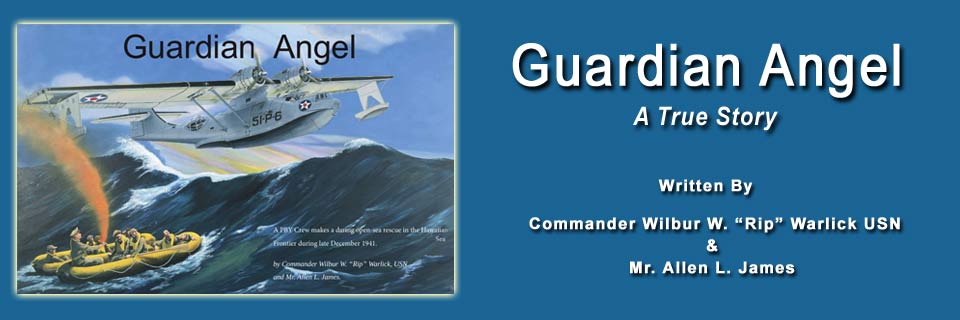

Guardian Angel -- A True Story

Chapter Six

Fisler quickly drafted a message to flight control reporting the time and location of the sighting, the estimated number of occupants in the rafts and a request for instructions. The message carried an urgent signal which meant it would receive immediate attention at the highest level. I felt a cold chill up and down my spine as I quickly and smoothly tapped out the message in Morse code. To that point in time, it had to be one of

the most exciting moments of my career as an aviation radioman.

While waiting for instructions from Pearl, some ingenious crew members assembled a small care package of canned date nut bread, several fruit juices and an unbreakable jug of water. The gift pack was then secured to an inflated life jacket. On one of our low passes, we successfully dropped the bundle within retrieval range of the two life rafts. Needless to say, the parcel was received with great exuberance.

Meanwhile, the pilots on the flight deck were engaged in an intense conversation, frequently punctuated by hand motions simulating aircraft maneuvers. I presume the rest of the crew, like I, began to feel that an open sea landing might be in the offing. At approximately 1400, the reply started to come in. Gimber peered anxiously over my shoulder as I converted the brisk incoming Morse code into words on my radioman's typewriter. Pearl Harbor informed us that there were no known friendly forces missing in our area, and that the nearest rescue vessel was about 48 hours away. They ordered us to drop emergency provisions and to continue our patrol. It was obvious that headquarters had written off the occupants of the rafts as unfriendly forces. As I handed the finished message to Gimber, I felt the orders were not going to sit well with Fisler. And I was right!

anxiously over my shoulder as I converted the brisk incoming Morse code into words on my radioman's typewriter. Pearl Harbor informed us that there were no known friendly forces missing in our area, and that the nearest rescue vessel was about 48 hours away. They ordered us to drop emergency provisions and to continue our patrol. It was obvious that headquarters had written off the occupants of the rafts as unfriendly forces. As I handed the finished message to Gimber, I felt the orders were not going to sit well with Fisler. And I was right!

Moments later, Fisler came on the intercom and told the crew of Pearl Harbor's instructions. Then, in a very serious voice, he said, "Guys, we have a monumental decision to make. There are eight to ten human beings in those two life rafts. If we carry out our orders and depart this area, their chances of rescue or survival are probably zero:' This conjecture was easily confirmed by the extreme difficulty we were having in keeping

the rafts in sight because of the poor weather conditions. "It is the consensus of the pilots that a successful landing and rescue can be carried out, despite the fact of one significant disclaimer. Neither Ensign Gimber nor I have ever participated in an actual openness landing. On the other hand, Snuffy has been the pilot in at least two successful operations of this type. If we can get permission to make the rescue, I will need to rely heavily on Snuffy's experience and guidance. Finally, because of the danger and high risk involved, I will not ask for permission to attempt the rescue unless there is unanimous consent and approval by the crew. So, what will it be?"

There was silence on the intercom. At this moment I thought of Ernest Hemingway and his novel, For Whom the Bell Tolls, as I looked up at the flight deck and then out my window. Was this our lost cause to champion? Yes, we must be faithful to the challenge, and success can come from a clear mind that accepts the possibility of failure and death. But what do we have to lose? As these thoughts ran through my mind, the ad hoc votes came in one by one. I engaged the intercom while realizing that Hemingway's tragic vision of mankind was his and not mine or this crew's.

The final vote tally was seven ayes and zero nays! It was time to go to work.

(Come back next Saturday for the continuing drama of Guardian Angel - A True Story.)

How Did They Get There

About midday on 30 December, Lieutenant Cooper and his crew again spotted an aircraft. They shot their last flare with great hope and were happy when the aircraft responded. They recognized it a a Navy PBY-5 and were very grateful when the Catalina crew dropped them some food and water. But, they also knew they would have to wait for a ship because the sea was far too rough for a Catalina to land.

Guardian Angel

Guardian Angel